An Elegant Italian devotional figure

The tradition of dressed and bejewelled devotional sculptures dates back to Antiquity, survives during the Middle Ages and increases between 16th and 18th century, both in Italy and throughout Catholic Europe. Between Renaissance and Baroque, the evidences are extensive and articulated, although the results aren’t always aesthetically and artistically convincing.

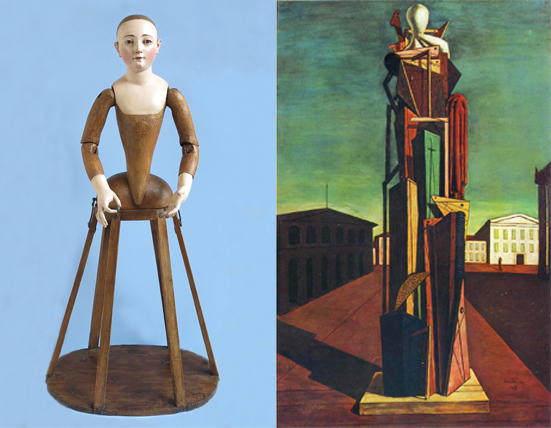

However, there are carved figures – as in the present example – made by excellent sculptors; even these best quality sacred sculptures – since they have been designed to be dressed – were often carved and finished merely in the upper part, showing a fine polychromy in the visible parts only (face, décolleté and hands).

Instead, the lower part of the figure (legs and feet) was made up of a simple truncated cone structure with splints, designed to support a heavy skirt; the bust – often held by hooks for being detachable from the base – rested on it, and had articulated arms, a recurring feature from the 17th century onwards.

Here, the elegant pose, the tender expression, the seraphic and forward-looking gaze (the eyes are made of glass paste), the refined hands, all these are signs of an eloquent and careful naturalism; the right hand holds a blue grain between the thumb and index finger while the left, with the palm facing upwards, probably held the other end of a Rosary and it is therefore likely that, once dressed, this sculpture represented a Madonna of the Rosary, according to an iconography very common in Central and Northern Italy.

The great devotion to Our Lady of the Rosary in fact led to the foundation of several dedicated confraternities, which often were the patrons for this kind of artworks.

The interest in these particular sculptures, mainly depicting female figures (Madonnas or female Saints), is not only artistic and devotional but also ethnographic, anthropological, sociological, historical and theatrical.

For example, the rite of dressing was the prerogative of a few privileged women, who often inherited this desirable task from their families. Today these statues are even more rare and interesting because we know that, in the first half of the twentieth century, many of them were lost: bishops, worried by the decency and the contrast of superstition, ordered their replacement, but often the faithful, supported by local parish priests, hid a good number of these sculptures, thus sparing them from their control.

The fascination of these sculptures “comes from the convergence in these objects of numerous processes of our relationship with the vital dimension of the sacred, a millenary relationship fully belonging to the history of humanity, becoming a domestic and daily one” (Bortolotti, 2011); moreover, to our contemporary eye, these figures acquire a particular metaphysical allure recalling the suspended atmospheres of two great Italian painters of the 20th century: De Chirico and Carrà.

DEVOTIONAL FIGURE

Polychromed wood

Northern Italy

Late 17th – early 18th century

Cm 38 x 85h

References: In confidenza col sacro. Statue vestite al centro delle Alpi, exhibition catalogue edited by F. Bormetti, 2011, fig. 11, p. 272-275; ; L. Bortolotti, Vestire il sacro. Percorsi di conoscenza, restauro e tutela di Madonne, Bambini e Santi abbigliati, 2011.

© 2013 – 2024 cesatiecesati.com | Please do not reproduce without our expressed written consent

Alessandro Cesati, Via San Giovanni sul Muro, 3 – 20121 Milano – P.IVA: IT06833070151