A wonderful Pair of gilded Phoenixes

These rare and unpublished metal sculptures were made by riveting together several foils of embossed iron, polychromed with red on the inner side and then fully gilded. The birds rest their talons on what looks like a rock or a drift of burning ashes, with little grassy tufts or small tongues of fire, placed over a circle of long feathers alluding to a nest, also made of embossed and gilded iron foils. These hollow sculptures stand on a lathed wooden base with a flared, polychromed and gilded profile.

The myth of the Phoenix, a long-lived bird capable of resurrecting from its own ashes after death, has its roots in oriental culture and probably derives from the ancient cult of the Sun.

It is a truly poetic picture linked to the Phoenix enchanting appearance and to its strong utopian meaning: this mythological being embodies the possibility of the constant renewal of life, a metaphor for the cycles of nature and the succession of the seasons.

The myth was absorbed into the Classical mythology: in Western culture it is for example recorded by Ovid who, in his Metamorphoses and Amores, enhanced the particular beauty and eternity of this marvelous animal.

The Phoenix strongly revives also in the Christian world, which reads the myth as a Christological metaphor of the Resurrection, thus interpreting the figure as a symbol, if not a true emblem, of Christ himself, of faith in the Almighty and of the capability of the soul to abandon the prison of the body.

In the European Renaissance culture, the Phoenix often recurs in contexts related to the themes of fire, revenge, of divine and knowledge, and is typically found in the realm of alchemical practices.

But perhaps the Baroque period, in particular, pays the greatest attention to the Phoenix: praised as an icon of transformation and show, change and surprise, it perfectly embodies the very themes of seventeenth-century culture; in literature, the Phoenix (associated with epithets such as divine, eternal, winged, glorious, noble, immortal) becomes thus immediately the protagonist of powerful metaphors linked to the imperial, heroic and divine world, and it is certainly in this sense that it is particularly beloved during the Rococo period. This interpretation of the myth in a celebratory meaning, for example, is well attested in the Baroque poetry of Spanish culture, not by chance the same one that made the splendid pair of Phoenixes presented here.

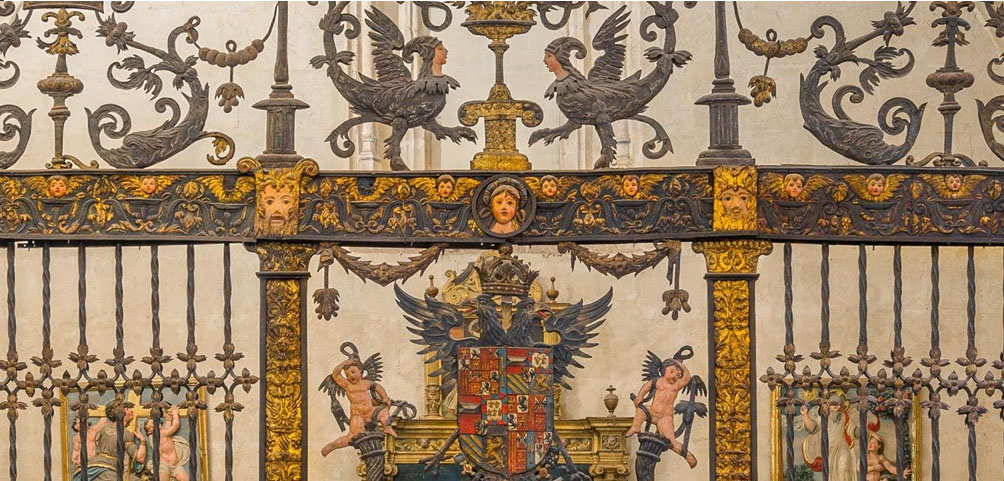

We can confirm the Spanish provenance of our Phoenixes because of their remarkable quality and technical features, which are fully consistent with the famous Iberian tradition. It is well known that between the 16th and 17th centuries, Spain developed an important figurative production in embossed and gilded iron, culminating in the numerous decorative panels enriching the famous monumental gates placed in some of the country’s major cathedrals (Salamanca, Sevilla, Granada), but also used to embellish window grilles, floor candlesticks and other decorative elements. As far as chronology is concerned, we can say that these two ironworks are still reminiscent of the great Renaissance tradition, but they were most probably made during the 17th century.

Until now the identification of similar iron Phoenixes has not been possible; therefore, establishing from which Spanish region they come from, is rather complex.

We can, however, recall two important examples of Phoenixes adorning famous Spanish monuments, albeit in different contexts and materials. In both cases, the Phoenix was chosen to protect places of great importance, as the ultimate image of power and knowledge.

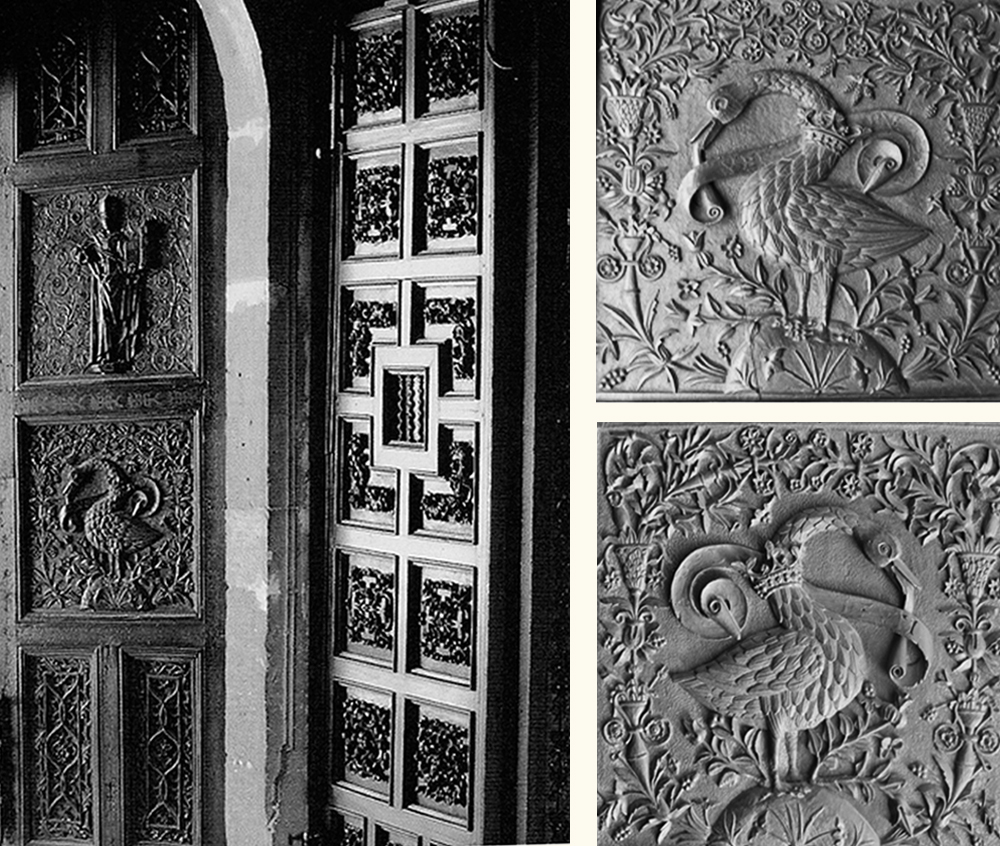

In the Santa Cruz monastery in Valladolid, the ancient finely carved wooden doors to the library, attributed to the sculptor Alejo de Vahìa and made around 1450-1500, are still in place: there, surrounded by a vegetal candelabra wreath, with a crown around their necks, two Phoenixes hold a scroll in their beaks, with the inscription Apud Deum in one, Verbum Erat in the other, from the well known incipit of the Gospel of John.

We find the Phoenix as the central image of the Casa de Castril monumental portal (Granada, now housing the Archaeological Museum), dated 1539. The Palace, located in one of the most important town centre streets and designed by the architect Sebastián de Alcántara, a disciple of Diego de Siloé, had belonged to the family of Hernando de Zafra, a man of letters and secretary to the Catholic Monarchs, Fernando II of Aragon and Isabel of Castile, and is one of the best examples of Renaissance architecture and decoration in the city.

It will be noticed immediately how, not by chance, in both cases the bird decorates and stands over a threshold, which should be considered as an actual passage but also as a symbolic space: in the case of the Valladolid library, the doors allow those who cross them to leave the earthly world and enter the sacred one through absolute knowledge, offered by the word of God and the writings of the Doctors of the Church housed in the library, i.e. a temple of wisdom; in Granada, the Phoenix dominates the entrance to the home of an important man, wishing to convey a clear message of power, through the image of a very ancient symbol of immortality and therefore, by translation, of omnipotence.

Going back again for a moment to the doors of Valladolid, one can also observe that the Phoenixes appear as a pair in a scholarly context: a licence to the traditional version of the myth confirming the possibility that this legendary bird, although known as a single one, was ‘doubled’ in the past for iconographic and decorative needs.

Both examples, made about a century apart and placed in two quite distant places, but equally relevant to Spanish history in the Catholic era, show us how the myth has spanned centuries and regions.

In addition to the symbolic interpretation, a further hypothesis should be considered for our two sculptures, namely the heraldic one: starting from the emblematic value of the mythological creature, the Phoenix was employed in coats of arms as an image of the perseverance of noble and generous souls and also of immortality. Several Spanish families bear the Phoenix on their coat of arms: the Campaners of Mallorca with the motto Fenicis instar vives, nomen campane sonavit; Francisco Boix de Berard, an important Majorcan nobleman, who used a uniform with the Phoenix in the flames with the motto non confundar in eternum; the Folquer (Catalonia) and Carnicer (Aragon) families who also had Phoenixes on their coats of arms.

It is therefore possible to assume that the works examined here held an important position in a representative room of a palace or in an aristocratic chapel, perhaps guarding a threshold, alluding both to the moral qualities and rank of the commissioning family, and maybe also directly to its coat of arms.

PAIR OF PHOENIXES

Embossed, polychromed and gilded iron

Spain

Late 17th century

Cm 51 h.

References: Ovid, Metamorphoses, XV, 392-410; Amores, II, 6, 5; The Faith in God, tapestry by Jan Van Brussel, post 1528, Paris, Musée national du Moyen Age – Thermes de Cluny; El mito del Ave Fénix en la poesía barroca novohispana: influencias y relaciones comparadas, Jorge García-Ramos Merlo, in El largo viaje de los mitos Mitos clásicos y mitos prehispánicos en las literaturas latinoamericanas, ed by S. Tedeschi, 2020.

© 2013 – 2024 cesatiecesati.com | Please do not reproduce without our expressed written consent

Alessandro Cesati, Via San Giovanni sul Muro, 3 – 20121 Milano – P.IVA: IT06833070151